The Hawaiian Nightingale: Ululani Robertson (1890-1970)

Portrait of Ululani McQuaid Robertson. Photographer unknown. Honolulu Star-Bulletin, October 14, 1939.

Among the few students selected for private study with Madame Sembrich was soprano Ululani Mcquaid Robertson Jabulka. Known fondly to Sembrich as her “little tropical flower,” Ululani travelled over 5,000 miles for the opportunity to study with the famed Polish opera star. She went on to garner fame in Italy, France, and Belgium as one of the definitive interpreters of the title role in Giacomo Puccini’s Madama Butterfly. However, as soon as she achieved acclaim on the major stages of Europe, she retired, returning to Hawaii in 1932. In her retirement, she became well-know as a civic leader and tireless advocate for arts and music in Honolulu and for Hawaiian statehood.

Aside from her accomplishments on the European stage, who was Ululani McQuaid? How did she come to study with Sembrich? Why did she choose to retire from the operatic stage at the height of her fame? Discover these answers and more in this curated portrait of the “Hawaiian Nightingale.”

Early Life (1890? - 1911)

An early portrait of Ululani Robertson. Artist Unknown. Honolulu Star-Bulletin, July 22, 1913.

Born in Honolulu on January 5, 1890 (approx.), Ululani McQuaid was the daughter of James H. McQuaid, an Englishman, and Kapulani Kalola Nahienaena Leinaholo Papaikaniau, a native Hawaiian and descendant of ali’i (Hawaiian royalty and nobility) from the islands of Maui and Hawaii. According to Ululani’s recollections, she was primarily raised by her grandmother and attended the Sacred Hearts Academy, a Catholic school which was popular among the Island’s wealthier residents. The school was staffed mostly by Belgian nuns and Ululani grew up speaking Hawaiian, French, and English.

There is little known about Ululani’s earliest years, beyond information given in interviews conducted later in her life. Even her exact year of birth remains unclear as there is no birth record available and various obituaries listed her as 75 or 80 in 1970. Musicologist Dale E. Hall, who published a brief biographical portrait of Ululani in his 1996 article Two Hawaiian Careers in Grand Opera, was able to locate the 1910 census records which indicated her age as 20, establishing her probable birth year as 1890. Hall also went so far as to contact the Sacred Hearts Academy which was unable to confirm any records of her attendance at the school.

Ululani married Alexander George Morison Robertson, a Hawaiian attorney and jurist, on May 29, 1907. After her wedding, she begins to appear in newspaper records as Mrs. A.G.M. Robertson, and her activities are more closely documented in the social columns. The earliest clippings found describe her as a hostess for celebrities and dignitaries visiting Honolulu and the Hawaiian Islands.

A.G.M. Robertson (1867-1947)

Alexander George Morrison Robertson was an attorney and the son of a distinguished associate justice of the Hawaii Supreme Court. In 1894, he was a delegate to the Hawaiian Constitutional Convention and served as a member of Governor Dole's staff. In 1895, he was appointed Deputy Attorney General of the Republic of Hawaii and also served three terms in the House of Representatives. President Taft appointed Robertson to the United States District Court in 1910. A year later, he was appointed Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Hawaii. In 1918, he resigned from the bench and became an integral part of the Hawaii Equal Rights Commission, which fought for equal rights and legal protections for citizens of the Hawaiian Territory. (Public Domain Photograph).

Early Training and the Beginning of a Career (1912-1920)

An early photograph of Ululani Robertson. Photograph by Perkins. The Honolulu Advertiser, December 8, 1914.

It is likely that Ululani was introduced to singing by her grandmother who was a well-known Hawaiian chanter, and who probably instilled in her a deep reverence for the Hawaiian language and song traditions. In the early years of her marriage, Ululani began taking lessons with mezzo-soprano Elizabeth Mackall, one of Honolulu’s most noted voice teachers. Mackall helped to build Ululani’s knowledge of Western art music and develop her technique and repertoire.

Ululani’s first recorded recital appearance was in 1912 on a program featuring several of Mackall’s students. The next year, newspaper records give accounts of at least seven performances, both public and private. Ululani began incorporating musicales into the parties she hosted at her home.

Aside from her budding talent as a singer, Ululani was a noted hostess in Honolulu’s social circles. Both the Honolulu Star-Bulletin and the Honolulu Advertiser, Honolulu’s largest and second largest news publications, praised the grandeur of events she hosted. An active member of her community, she was a member of the Morning Music Club and The Outdoor Circle, and was a founding officer of the Hawaiian Art Society.

As a result of Ululani’s talent, gracious personality, and social position, her popularity continued to increase between 1914 and 1920. She began appearing as a featured soloist with local churches and choral groups around Honolulu, receiving enthusiastic encores and splendid reviews from local newspapers.

Ululani Robertson (right) planting the Christmas tree at Iolani Palace as incoming President of the Outdoor Circle from 1919-1920. Honolulu Star-Bulletin, September 11, 1977.

Two notable performances in 1918 solidified the young Ululani’s place in Hawaii’s musical community, the first being a solo recital given for the benefit of the Red Cross at Honolulu’s new Mission Memorial Hall, and the second a feature in a Hawaiian musical given by Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole.

During World War I, the citizens of Hawaii did a great deal to support relief efforts, raising money and collecting clothing and food supplies. Ululani offered her talents as a singer, performing for events for Army and Navy groups stationed in the islands. Honolulu’s Ad Club sponsored a recital to benefit the American Red Cross on April 26, 1918 featuring Ululani Robertson (billed as Mrs. A.G.M. Robertson). Her program was a success, with nearly every seat filled. Encores included several Hawaiian songs, a tradition that the young singer would continue throughout her career. The concert was so well received that she was, from then on, known to the public as the “Hawaiian Nightingale.”

Later that year, with her notoriety as “Hawaii’s Nightingale,” Ululani was featured in a hookupu (traditional Hawaiian welcome ceremony for visiting nobles & dignitaries) given by Hawaii’s US Congressional delegate Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole. The event was a welcome for US Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane. On this program, Ululani performed traditional Hawaiian songs accompanied by ukuleles and a glee club from the Kamehameha Schools. Through this event she displayed herself not only as a fine singer of western art music but of the traditional and popular music of Hawaii. Throughout her life, Ululani would maintain her passion for performing and preserving the music and language of Hawaii.

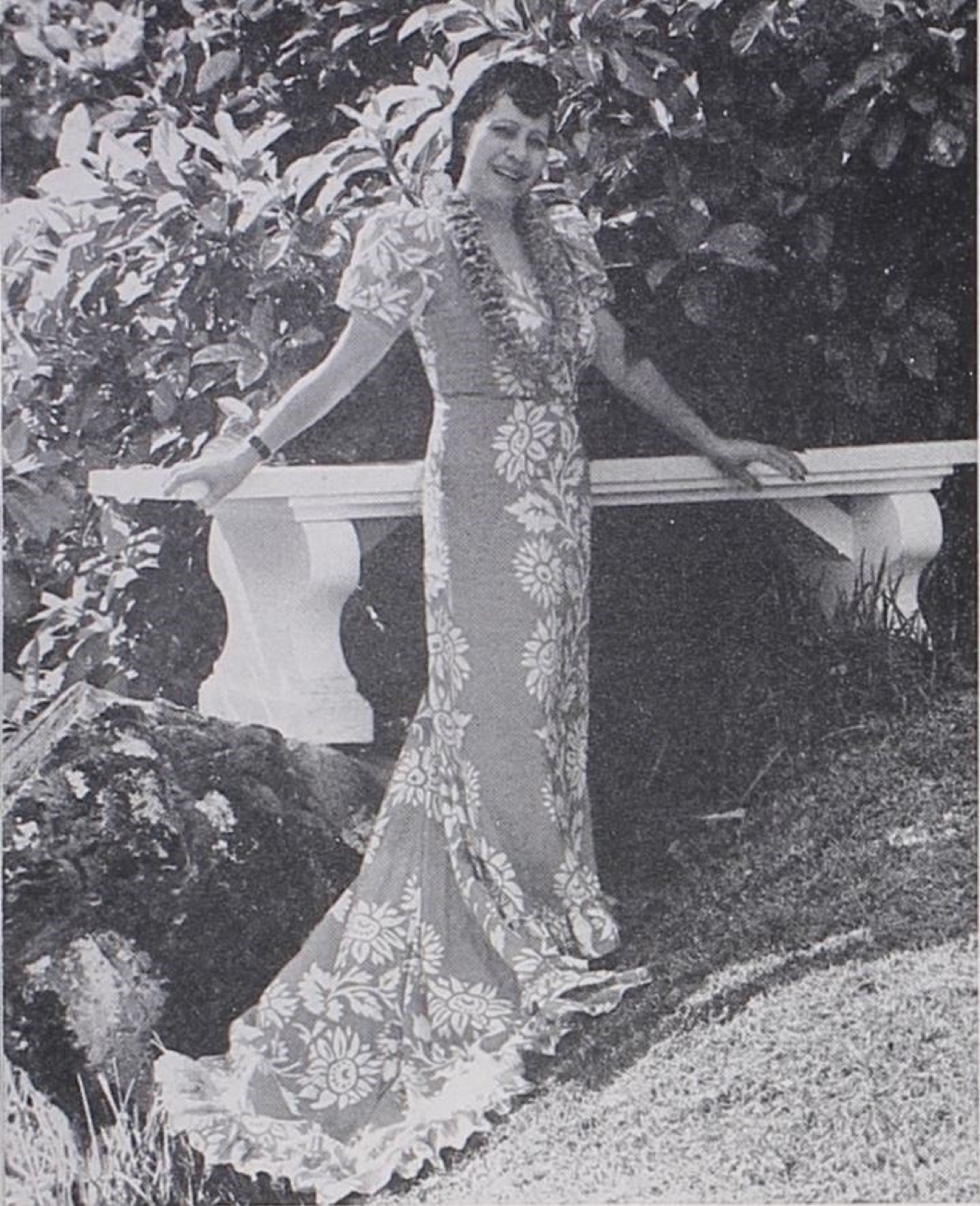

Ululani as she would appear when performing Hawaiian programs. Photographer Unknown. The Honolulu Advertiser, December 10, 1933.

Royalty and dignitaries gathered for the 1914 Kamehameha Day Celebration. Ululani was on the finance committee for the celebration. Front row from left to right: Justice A.G.M. Robertson, Ululani McQuaid Robertson, Princess Elizabeth Kahanu Kalanianaʻole, Queen Liliʻuokalani, Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole. Photograph from the Library of Congress.

Ululani continued performing and studying with Elizabeth Mackall. Sometime in late 1919 or early 1920, Mackall moved to San Francisco, California to join the music faculty at Mills College. Ululani took an apartment in San Francisco, travelling from Hawaii for periods of study with Mackall until 1921.

Study with Sembrich (1921-1925)

Having studied with Mackall for over a decade, in the spring of 1921, Ululani made the decision to seek a new teacher to further her musical accomplishments. Despite little connection to the musical world outside of Hawaii, she decided to seek an audition with Marcella Sembrich after reading an interview with the great prima donna in Mable Wangall’s 1899 book Stars of the Opera.

“When I went to New York I wanted to study with Madame Sembrich, not because someone had told me to go to her, but because I had read so much about this glorious woman. I had no letter of introduction to her. There was a long waiting list, so the secretary informed me.”

The Sembrich Collection contains a copy of Wangall’s 1899 book that inspired Ululani to seek out the great Polish diva. The interview she read describing the great Polish diva’s kind nature has been digitized and is available below:

Having set her mind to meeting the renowned Sembrich, Ululani prepared to travel to New York. Her trip was hindered initially by a burglary at her San Francisco apartment and then when she contracted mumps on the long train ride. She arrived in New York City, but her prolonged illness delayed her seeking out Sembrich and caused her to miss Enrico Caruso’s final Metropolitan Opera performance, which she was to attend with fellow Hawaiian opera star tenor Tandy Mackenzie. After recovering, she began working to arrange her meeting with Madame Marcella Sembrich. After travelling five thousand miles and facing various trials and tribulations, her chance came on Easter Sunday of 1921.

Despite having no letter of introduction, the secretary spoke to Sembrich who decided to hear the singer and have a luncheon to discuss Ululani’s ambitions as a singer. Another interview recounts the audition with Sembrich:

“The studio accompanist, hard-working fellow, brought the song to a close with a resounding chord. Its soft, somewhat sad, melody had been strange to him, and its words stranger still, for it was a Hawaiian bit about the rain and a drenched flower.

The singer, resting now by the piano, gathered herself together for the verdict. She had come five thousand miles from Honolulu to ask the great Marcella Sembrich to teach her. And Mme. Sembrich was before her now, about to decide.

She speaks. “Where, my dear, did you come upon such – shall I say – Chinese-Italian? So was habe Ich nie vorher gehört.” (tr. from German: I have never heard this before”)

The singer, for all the fact that this audition was for her a solemn affair, had to laugh.

“That, Madame, was not Italian at all. It was Hawaiian.”

“Ah so,” breathed the great teacher, “you come from those islands out there in the Pacific, to have Sembrich teach you? Well, we shall see!”

Following her audition, Sembrich asked the young Ululani what she desired from a career in music. She boldly told Sembrich that she had no ambition for a career, only to perfect her voice and her art. Following her audition and interview, Sembrich sent Ululani off to await a decision. After three days passed, Sembrich contacted Ululani to accept her as a pupil, only on the condition that she pursue a career. She immediately took an apartment near Manhattan’s Bryant Park and set to study. Ululani and Sembrich worked well together and Ululani was soon fondly called Sembrich’s “little tropical flower.”

In the summer of 1921, Ululani travelled with her new teacher to “The Maples,” Sembrich’s Adirondack retreat in Lake Placid, New York. It was there that the only known photographs containing both Ululani Robertson and Marcella Sembrich in the same image were taken. These photos remain in The Sembrich’s collection and can be viewed below:

Students with Marcella Sembrich at “The Maples,” in Lake Placid, New York. Marcella Sembrich stands at the center of the back row. Ululani Robertson pictured seated left. Photograph by G.T. Rabineau. 1921. From The Sembrich Collection. Click image to enlarge

Students with Marcella Sembrich on the front lawn of “The Maples,” in Lake Placid, New York. Ululani stands to the far left and Mme. Sembrich stands fourth from the left. Photograph by G.T. Rabineau. 1921. From The Sembrich Collection. Click image to enlarge

“All pupils loved my teacher. It made no difference whether they were successes or failures, they never forgot her magnetic personality. I spent my first summer with Mme. Sembrich at her home in Lake Placid. She herself was a marvelous cook and she planned her menus each day. I remember a little squirrel who, each summer, came to the back kitchen door to be fed by Madame. I think he got his winter store of nuts from her. Like people, he never forgot the gracious woman.”

An advertisement for Ululani Robertson’s performance at Mission Memorial Hall on July 12, 1922. Honolulu Star-Bulletin, July 10, 1922.

For the next four years, Ululani alternated between periods of study in New York and trips to Honolulu to visit family and give performances. It is during these years that her billing for concerts now included the line “Artist Pupil of Mme. Sembrich.” Reviews praised her abilities and her fine coloratura voice. Ululani, much like her Sembrich, was also known to accompany herself for encores, playing the piano or ukulele.

Sembrich moved her Adirondack summer retreat to Bay View, an estate on the shores of Lake George, in the summer of 1922 and purchased the property the following winter. Ululani was among the first students, along with sopranos Dusolina Giannini and Queena Mario, to take lessons in Sembrich’s new teaching studio (today The Sembrich) which was completed 1924.

Reviews indicate that Robertson showed great improvement in stage presence and the finer details of her artistry following only a year of study with Sembrich:

“Her dulcet tones, always so appealing to her many admirers, have developed a range, a power, a flexibility and a depth of feeling which have lifted her from the mere amateur class into that of the semi-professional, as all who hear her at her concert next Wednesday will agree. One year under the direction of such a noted singer has done so much for Mrs. Robertson, that one can have no doubt that in the next year’s work, which she is planning, she will easily reach the goal for which Madame Sembrich sets for her most promising pupils, a successful New York appearance.”

An autographed photograph of Marcella Sembrich as Mimi in Puccini’s La Bohème, dated December 1921, with the message: “To dear Ululani Robertson with affectionate remembrance.” The Honolulu Advertiser. January 20, 1935.

Ululani returned to Lake George and New York City for extended periods of study alongside Sembrich’s students from the Curtis Institute and the Juilliard Graduate School, where she was director of the vocal programs. During her studies with Sembrich, Ululani began studying the roles of Mimi (La Bohème) and Cio-Cio-san (Madama Butterfly) by Puccini. Sembrich worked with Ululani to refine her diction, stage presence, and musicality, preparing for for a grand debut. However, the New York City debut that was the standard for Sembrich’s pupils never came as was decided between singer and teacher that a trip abroad for European study was more advantageous than an expensive Aeolian Hall debut:

“Mme. Sembrich felt that I should have European study. So, with my husband’s approval, I sailed for Italy and studied with Professor Guisseppi Benvenuto. I had already had four years of study with Mme. Sembrich. But there were languages to be studied, stage deportment, and a repertoire to be built up. I also had a few lessons with Mascagni, author of the opera, Iris, which I was studying.”

One of Ululani’s final performances as a pupil of Sembrich was in September of 1925 in the Italian play “Scampolo.” The event was held in the studio of Lake George resident and Sembrich pupil Polly Hoopes on her estate Stillwater. Following her final summer in Lake George, Ululani set sail for Milan, Italy to further her studies in Europe.

Further Study and European Career (1926-1932)

Following Sembrich’s advice, Ululani sought out several European teachers to help further her musical education, beginning in Milan, Italy.

While there, she took lessons with Giuseppe Benvenuto and Pietro Mascagni, studying roles from Puccini’s Madama Butterfly and La Bohème, Mascagni’s Iris, and Charpantier’s Louise. Ululani then set her sights on France, particularly Paris, for further study. She continued her preparations for a European debut with pianist John Byrne. In 1926, she made her concert debut at the Salle Comedia in Paris and garnered positive reviews, particularly for her inclusion of several songs from Hawaii.

“Miss Ululani Robertson, who had chosen the Salle Comedia for her concert, possesses a very pretty soprano voice with exquisite crystalline notes. She knows how to sing, she sustains a note and reaches the pianissimo with undeniable art... Where she was quite remarkable was in some “Lieder” by Grieg; in “The Answer” by Terry, which she was obliged to repeat, and, above all, in some Hawaiian songs, to which she gave a really artistic expression. The “Na Lei O Hawaii” by King, won her a unanimous encore.”

Following her successful concert debut, Ululani began appearing for social club events and private salons in Paris. In April 1927, she made her operatic debut in the title role of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly in Bordeaux, France. Despite singing the role in Italian instead of French, which was customary in French opera houses, critics were enamored by her vocal ability and refined acting. Her debut was followed by 22 more performances of the role across the continent. Her career took her to Austria, Czechoslovakia, France, Italy, Germany, and Spain where she appeared on stages in Deauville, Florence, Liège, Leipzig, Lyons, Milan, Prague, Rouen, Vienna, and more. Billed as “Madame La Princesse Ululani,” news outlets praised her interpretation of the role, deeming her “an artist of unusual merit” and characterized her singing as “ravishing,” “charming,” and “superb.” Near the end of her tour, several news articles in Europe reported that Ululani would return to Honolulu to perform the role in 1928.

The photograph that accompanied news of a successful Paris debut. Honolulu Advertiser, August 7, 1936

Ululani As Butterfly in 1928. Photographer Unknown. Paris. Honolulu Star-Bulletin, December 16, 1933

Robertson as Butterfly in 1928. Photographer Unknown. Paris. Honolulu Advertiser, July 27, 1941

However, Ululani did not return to Honolulu and instead began study at the American Conservatory in Fountainbleau around 1928, coaching with pianist Camille Decreus, the long-time accompanist of the Polish Tenor (and friend of Sembrich) Jean de Reszke. During her studies, she continued to appear in concert and opera across the continent and her popularity in the European musical scene began to grow.

During this time in Europe, nationalism was a prevailing trend in the musical world. Folk songs, particularly those sung in original native languages, were garnering attention as the true expressions of national culture and identity. Ululani, being one of so few Hawaiian singers to achieve European fame, was made even more popular by her renditions of Hawaiian songs, her ukulele accompaniments, and her displays of Hawaiian dance for European audiences. Among the Hawaiian songs presented by Ululani was the popular song Na Lei O Hawaii by Hawaiian composer Charles E. King.

To date, no original recordings of Ululani’s singing have been located. The Victor Talking Machine Company has notes of two recordings recorded by Ululani in 1923, however, neither made it to publication. While Ululani was in Europe, another “Hawaiian Songbird,” named Lena Machado, began recording and popularizing the music of Hawaii in the United States. Machado’s 1928 recording of the work with traditional instrumental accompaniment is a definitive representation of the traditional Hawaiian vocal technique ha’i which is characterized by a distinct break between vocal registers and accompaniments.

Portrait of Ululani from the Paris Times. July 18, 1926. Source: gallica.bnf.fr / BnF.

Prior to her entrée to the European opera scene, Ululani was offered a position as a Hawaiian singer with a touring band. While she loved to sing the songs of Hawaii and perform the popular music for audiences, she still believed that the role of Butterfly best suited her. Although the operatic stage was her chosen home, Ululani did appear on several occasions performing popular Hawaiian music. One such instance was with a Hawaiian orchestra at the Colonial Exposition in Paris in 1931, which was broadcast on the radio and was heard by Ululani’s husband A.G.M. Robertson in San Francisco.

Ululani toured across Europe appearing as Madama Butterfly and occasionally in other roles such as Mimi in La Bohème. Then in 1931, it was announced that Mme. Ululani was to appear for several performances of Madama Butterfly at Paris’ Opera Comique, one of the most celebrated European venues with perhaps the most discriminating audience. This was the first time a Hawaiian opera singer would appear on the stage of the famous opera house. The night of her debut, Madame Sembrich cabled her fondest congratulations. Ululani’s husband even travelled from Honolulu to see her take the stage in Paris.

News of her lauded debut was announced in papers across the United States. Her achievements on the stage of the Opera Comique were the pinnacle of her international fame and solidified her place as one of the leading interpreters of Puccini’s Butterfly. The Parisian Critic Louis Schneider published this review of the Opera Comique performance in an unidentified Paris newspaper:

Louis Schneider, music critic, writes in a Paris newspaper…

Madame Ululani sang “Madama Butterfly” at the Opera Comique, on Monday night. Her carriage and extreme grace give her an exacting possession of the role in which she proves the fullest depths of the character in her interpretation. Her voice, although not of great volume, is sufficiently ample for the role; and if, on entering the stage, she was overcome with emotion, she affirmed herself in the succeeding acts with charm and beauty of her voice, and the seizing tenderness of her intonation. She sang quite remarkably “Sur la mer calmes,” and also the Berceuse. Her success was decisive and mounted act by act.

– from an unidentified French publication. Translated and printed in the Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Page 26. January 2, 1932.

Image: Robertson Cio-Cio San at the Paris Opera Comique (ca. 1931). Photographer Unknown. From The Sembrich Collection.

Despite her success on the stage in Paris, in 1932, Ululani stated that she was needed at home in Honolulu to take care of her husband, and thus made the decision to end her European career, having achieved the success she initially sought. She remained in Europe performing and exploring the continent with her husband until the latter half of 1933 when she began her journey home.

Return to Honolulu (1933-1948)

On Thanksgiving Day of 1933, the Hawaiian Nightingale returned to Honolulu with her husband aboard the Lurline. Friends and acquaintances gathered at the port to welcome the newly minted international star home, showering her with flowers and leis. While she had ended her European career, Ululani continued to make appearances in Hawaii and rumors of a contract with the Civic Opera of Chicago and offers from New York managers abounded, but none proved true or of any interest to Ululani.

Fun Fact

Upon her return to Honolulu, Ululani brought with her three Siamese cats she adopted while in Paris. The trio, Handsome, Poupoulle, and Big Boy, captured headlines and even won awards in the first official Honolulu cat show in 1935.

Ululani, like Sembrich, was a lover of nature and animals. In a 1953 interview, Ululani said:

“I am a great animal lover and I was always bringing home stray kittens to be cared for or little puppies who had no home. But I am especially fond of kittens.”

- from “Island Hostess” in Paradise of the Pacific. February, 1953.

Image: Photographer Unknown. Honolulu Star-Bulletin, December 23, 1933.

One of her first notable appearances upon her return to Honolulu was on an NBC live radio broadcast commemorating President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first year in office. Ululani was a featured soloist on this program. She performed a new composition by Charles E. King, dedicated to Mrs. Roosevelt, titled Makuahine O Ka Lahui.

Ululani Robertson. Photographer Unknown. Honolulu Advertiser, February 16, 1936.

Her debut with the Honolulu Symphony was initially scheduled for 1934, but was cancelled due to illness. Her debut with the Symphony finally came the next year when she appeared as a guest soloist, performing “Pleurez mes yeux” from Massenet’s Le Cid. Praise for her artistry was universal and the only critique noted was “the aria was too short.” Ululani continued to appear in venues across the islands and was ubiquitous with Hawaiian musical life in Honolulu.

In 1936, Ululani was able to, once again, display her talents as both an operatic prima donna and a champion of the music and traditions of Hawaii. In March, she appeared in a Hawaiian pageant reenacting the High Chiefess Kapiolani’s defiance of the volcano goddess Pele. Ululani took the lead role as the High Chiefess and scored great success singing traditional Hawaiian songs and melodies.

About two weeks later, the Morning Music Club and the Honolulu Symphony announced that they would launch a joint production of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly with Ululani reprising her signature role. This proved to be a highly anticipated musical event in Honolulu as it was the first time the opera would be staged in Hawaii. American Tenor Frank Colson, who performed under the stage name Aroldo Collini, was brought to Hawaii from Los Angeles to star aside Ululani as Lt. Pinkerton. The opening of the opera was delayed by a day due to illness. The next night, the production opened and proved to be the musical event of the season, earning generous plaudits from the press. This was the last time Ululani appeared in her signature role on the operatic stage.

Ululani Robertson as Cio-Cio-san and Betsy Sumner as Dolore in the 1936 production of Madama Butterfly at the McKinley Auditorium by the Morning Music Club and the Honolulu Symphony. Photograph by Terry Ogden. From “Island Hostess” in Paradise of the Pacific, February, 1953.

Ululani and company greet Aroldo Collini upon his arrival in Honolulu. Advertiser Photograph. Honolulu Advertiser, April 26, 1936.

Ululani greets Aroldo Collini upon his arrival in Honolulu. Advertiser Photograph. Honolulu Advertiser, April 17, 1936.

Ululani Roebrtson as Cio-Cio-san and Aoldo Collini as Lt. Pinkerton in the 1936 production of Madama Butterfly at the McKinley Auditorium by the Morning Music Club and the Honolulu Symphony. Star-Bulletin Photo. Honolulu Star-Bulletin, May 14, 1936.

“Outstanding in an evening of excellence was the lovely and meticulous singing of Mme. Ululani Robertson. Effective and convincing was her sympathetic portray of the fragile Japanese girl. Her singing was of a high order, her phrasing was that of an accomplished musician in full command of her role, and her high tones rang out with real splendor.

Mme. Robertson was considerate of every meaning of her music, her sense of dramatic values is schooled as it is in thoughtful European teaching and direction. Butterfly delighted by approaching the music through intelligence. A broad vocal sweep was evident in Mme. Robertson’s singing and she shaded her songs according to the meaning of the words.”

Over the next decade, “Hawaii’s Songbird” gave recitals, hosted musicales, and quickly reentered the social circles of Honolulu, becoming involved with local clubs and social groups including the Morning Music Club, The Outdoor Circle, and the Civic Club. In 1938, she was elected President of the Morning Music Club and began publicly advocating for the preservation of the music and language of Hawaii through a Hawaiian School of Music and presenting entire programs featuring the songs of Hawaii. Ululani was also featured in a serial column in the Honolulu Advertiser titled, “How’s Your Hawaiian?”

In 1941, following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Ululani once again became involved in relief efforts. Following the devastation from the bombing, Ululani opened her home to several displaced families. Gayle Andersen, who was 15 at the time, was one of those displaced. In a 2017 article, Anderson recalled:

“‘I was let loose,’ reminisced Andersen about her short but memorable time at the house. ‘I could go anywhere I wanted to during the day. Mrs. Robertson didn’t care, so I played up and down both sides of the bank [of the stream], and the stepping stones were [just] slightly in the water, so you could go across.’

Andersen remembers the formal dinners she enjoyed in the company of Robertson and the host’s regal appearance. She recalled the host’s elegant muumuus, trailed over her arms as she walked down the stairs. Andersen also remembers admiring Robertson’s old opera costumes. ‘She wanted me to take home some clothes. I was fifteen, but I [even though I] only weighed 115 pounds, I couldn’t fit any of them. I was too big!’ exclaimed Andersen.”

To read the full article about Gayle's experience, follow this link: WWII Survivor Visits HBA High School - Eagle Eye - January 2017

Ululani wears a traditional Holoku trimmed with lace at her home Lanihuil. Photograph by DeGaston. From “Island Hostess” in Paradise of the Pacific, February, 1953.

Part of the 13-acre grounds surrounding Ululani’s home Lanihuli. The name of the home means “looking heavenward” after the mountain peak that can be seen of the east lanai. Photograph by John T. Warren. From “Island Hostess” in Paradise of the Pacific, February, 1953. Click image to enlarge

Originally built by John W. Waldron in 1910, Clent Heath was one of the first concrete homes on Oahu. Waldron’s widow sold the home to her uncle, A.G.M. Robertson and it was renamed Lanihuli. Part of the Nuuanu stream cut through the estate and terraces offered stunning vistas. Today the grounds are the campus of the Hawaii Baptist Academy High School and the house serves as the administration building. Photograph by Crail, Hollywood, CA. From “Island Hostess” in Paradise of the Pacific, February, 1953. Click image to enlarge

The sitting room at Lanihuli, noted for its ohia wood paneling and floors, was the site of many of Ululani’s elaborate dinners and parties. She often felt that it was wrong to have such a beautiful spot all to herself, so she would invite convalescents from the nearby hospital to enjoy the grounds surrounding the home. Photograph by Crail, Hollywood, CA. From “Island Hostess” in Paradise of the Pacific, February, 1953. Click image to enlarge

Similar to her efforts during World War I, Ululani organized performances for troops stationed in Hawaii during the second World War. Through her involvement with the Hawaiian Civic Club she raised funds for the Red Cross and organized events for the sale of war bonds. She also chaired benefit events for the Civic Club and served a term as President of the organization.

Near the end of the war, in July 1945, fellow Sembrich student Dusolina Giannini visited Oahu to sing for members of the armed services stationed on the island. Giannini and Robertson had studied together under Madame Sembrich in New York City, Lake Placid, and Lake George. It is no surprise that Ululani insisted on hosting Giannini for her stay and, in elegant fashion, threw a grand reception for her friend and fellow artist.

Dusolina Giannini wears a Hawaiian Holoku and holds Ululani’s Siamese cat Big Boy. Star-Bulletin Photo. Honolulu Star-Bulletin, July 24, 1945.

Dusolina Giannini (left) and Ululani Robertson (right) with Siamese cat Big Boy. Photographer Unknown. Honolulu Advertiser, July 29, 1925.

An autographed headshot of Dusolina Giannini given to Marcella Sembrich. (Written in Italian) Photograph by M.I. Boris, New York. From The Sembrich Collection.

Ululani Robertson representing the Hawaiian Civic Club at the 1943 Kamehameha Day celebration’s war bond drive. Honolulu Advertiser, June 8, 1943.

Ululani Robertson (center) with other members of the board of Parks and Recreation for the city of Honolulu. Honolulu Advertiser, October 26, 1946.

Following the war, Ululani performed less frequently, instead focusing on her involvement with social clubs and organizations. In 1946, she was named to the board of Public Parks and Recreation in Honolulu and played a large role in the beautification of the city.

It is also suspected that during this time, her husband’s health was in decline. In 1947, A.G.M. Robertson passed away, leaving his estate to Ululani.

Second Marriage and Retirement (1948 - 1970)

Photograph by Murie Ogden. Honolulu Star-Bulletin, February 15, 1940.

In the final two decades of her life, Ululani rarely performed but stayed actively engaged in her community. In 1948, she remarried to Jan Jabulka, the managing editor of the Honolulu Advertiser. They held the event at Ululani’s home and her friends filled her home with flowers for the occasion. A small ceremony was held in the evening with the Nuuanu Valley as the backdrop.

In 1951, Jan Jabulka was named the Executive Director of the Hawaii Statehood Commission. The couple relocated to Washington D.C. and made their primary residence in the nation’s capital, working to secure statehood for the territory. Ululani anticipated that they would be away only three to four months. However, securing statehood for the Hawaiian Territory took nearly a decade. Reports of Ululani’s activities in Washington are scarce, but she does appear in attendance records for several events, occasionally singing by popular request. In 1959, Hawaii became the 50th state in the Union and the Jabulkas’ time in Washington DC came to a close.

Following Hawaii’s battle for statehood, the Ululani and her husband returned to Honolulu. Ululani was pleased to return to her Honolulu estate following nearly a decade living in apartments and hotels in Washington, DC. Ululani spent the 1960s as a socialite, presiding as a patroness of numerous club events. She passed away at her home in 1970 at the age of 80.

The Legacy of Ululani McQuaid Robertson Jabulka

Following her death, Ululani’s estate home passed on to the heirs of her first husband and was eventually sold. The building still stands and is the administration building for the Hawaii Baptist Academy’s High School. Her second husband inherited her Tantalus mountain home and the rest of her estate. The majority of her belongings were sold at auction in 1971, aside from a few items that were bequeathed to family and friends. Her collection of ali’i jewelry was donated to the Bishop Museum and still remains in their collection. Honolulu’s Morning Music Club, of which Ululani was a dedicated member, established the Ululani Memorial Voice Competition, as a tribute to the late singer. A 1934 poem dedicated to the Hawaiian opera star by Maryjane Kulani F. Montano also appears in several publications:

Manu Memele (Original Hawaiian)

Hooheno i ka lai ehukai

Lamalama po Mahealani

Ko leo, e ka manu hulu Melemele

Hoene malie i ka poli.

Mehe lehua pua kea a-la

E haaheo maila i ka uka

I po ke aha onaona

Ko leo, e ka Manu Memele.

Yellow Bird (English Translation)

Bewitching the ocean spray’s fair clime,

Brilliant as the full moon light,

Your voice, O bird of yellow plumage

Brings melody gently yo the breast

Like unti a pale yellow Lehua

Proudly blooming at the uplands

That pervadesits fragrant scent,

Is your voice, O singing bird.

In 1980, following the death of Jan Jabulka, a gift of $1,000,000 was bequeathed to the Bishop Museum for the construction of a new open air entrance pavilion in honor of his late wife. The Jabulka Pavilion was completed in 1982 and continues to serve as the main entrance to the museum. (click any image below to enlarge)

Ululani Robertson. 1939

Ululani Robertson, 1948

Ululani’s Steinway piano and ukelele sold at the auction.

Queen of Holoku Ball, 1950

The Jabulka Pavillion, 2007

Links to Additional Reading

Learn More About Hawaiian Music and Art and the Genre’s Cultural Influences:

Learn More About Two Stage Works Based on Hawaiian Culture:

Learn More about the History of Hawaii and its Monarchy:

About the Curators

Grace Ashley is a native of Falkville, Alabama. Ms. Ashley is currently pursuing her Doctor of Musical Arts degree at the University of Kentucky in Lexington, KY. She received Bachelor degrees in Vocal/Choral Music and Choral Education from the University of North Alabama and a Master’s degree in Vocal Performance and Pedagogy from East Carolina University in Greenville, North Carolina.

Ms. Ashley is an emerging young performer in Alabama, North Carolina, and Georgia, as well as various local churches and small venues in Alabama’s Shoals area. She has performed various opera roles during her undergraduate and graduate career. Her recent roles include Susannah in Susannah, St. Teresa I in Four Saints in Three Acts, Donna Anna in Don Giovanni and Mother Jeanne in Dialogues of the Carmelites. She currently teaches private voice along with other music courses at The University of North Alabama in Florence and Wallace State Community College in Hanceville. She is a founding member of the Walk with Me Foundation’s choir, SOLAS. She also is directing the Youth Choir for the Foundation.

Photograph by Jonathan Levin

Caleb Eick is a multi-faceted arts professional, maintaining an active life as a performer, scholar, and administrator. For The Sembrich, Caleb oversees development activities, educational outreach, strategic marketing, and curatorial affairs. As a scholar, Caleb researches, writes, and presents on historic operatic personalities from America’s “Gilded Age,” including Marcella Sembrich. When not working behind the scenes, Caleb performs as a soloist and in chamber music recitals with friends and colleagues from around the globe. Caleb is an engaging performer and dedicates the majority of his performing activities to art song and chamber repertoire.

A passionate advocate for the arts, Caleb sits on the Board of Directors for the Russian Chamber Art Society in Washington, D.C., and Klinkhart Arts Center in Sharon Springs, NY. He is currently completing professional studies Visual & Performing Arts Management at New York University and recently completed a fellowship with the Institute for Nonprofit Leadership & Community Development at SUNY Albany’s Rockefeller College of Public Affairs & Policy. Caleb holds a Master of Music degree in Voice Performance & Pedagogy from East Carolina University and a Bachelor of Arts degree in Voice from The College of Saint Rose.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to those who contributed their assistance in research for this article including Jodie Mattos from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library, Krystal Kakimoto from the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, and musicologists Christine Wisch and Dale E. Hall.

This project was created as part of the Museum Association of New York's Building Capacity, Creating Sustainability, Growing Accessibility program.

This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services [CAGML-246991-OMLS-20]. The views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this exhibit does not necessarily represent those of the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

About IMLS

The Institute of Museum and Library Services is the primary source of federal support for the nation's approximately 120,000 libraries and 35,000 museums and related organizations. The agency’s mission is to inspire libraries and museums to advance innovation, lifelong learning, and cultural and civic engagement. Its grant making, policy development, and research help libraries and museums deliver valuable services that make it possible for communities and individuals to thrive.

To learn more, visit www.imls.gov and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

About MANY

The Museum Association of New York inspires, connects, and strengthens New York’s cultural community statewide by advocating, educating, collaborating, and supporting professional standards and organizational development. MANY ensures that New York State museums operate at their full potential as economic drivers and essential components of their communities.

To learn more, visit www.nysmuseums.org and follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn.