Igor Stravinsky and the Premiere of the Century

Image courtesy of the Hungarian website https://fidelio.hu/.

Poster for the UK release of the film

May 29, 1913. Was there ever a more epochal moment in the annals of music history?

That’s the question posed by musicologist Charles M. Joseph in his book Stravinsky’s Ballets in describing the 1913 premiere of The Rite of Spring at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris. And it’s the question that we’re going to explore here today as we delve into the monumental premiere and the groundbreaking score that, “with its rebellious energy and its celebration of life through sacrificial death,” served as “a prelude to the Great War” and as a signpost to “the birth of modernism,” this according to writer Modris Eksteins in his book Rites of Spring.

To set the scene, let’s begin with a re-creation of that auspicious premiere from the opening segment of the 2010 film Coco Chanel and Igor Stravinsky, a masterful piece of film-making, produced by Claudie Ossard and directed by Jan Kounen. “The choreography is the original,” wrote Ms. Ossard in a recent email. “We redid the sets and costumes identically.” This re-enactment, with its sweeping camera angles and multiple perspectives from stage, audience and orchestra pit alike, conveys the energy and excitement of that first performance, from the initial murmurings of disquiet to the ultimate audience unrest that ensued---with Diaghilev flashing the theater lights to try and maintain order and Nijinksy barking backstage orders to his dancers from the wings. In my view, this is as close as we can come to imagining ourselves as eyewitness to the momentous event:

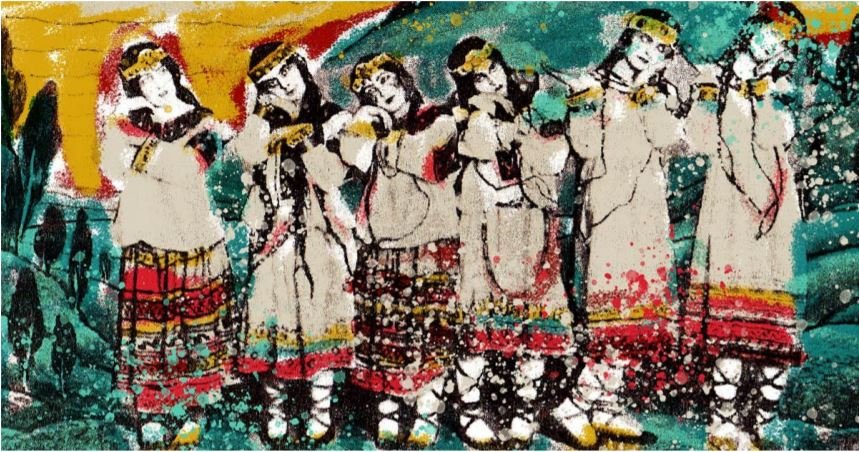

The third and final design for the first act set for The Rite of Spring by Nicholas Roerich. Courtesy of Northwestern University Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures. Click to enlarge

To probe more deeply into the details of that historic night, we turn now to selections from "Chapter Four, The Rite of Spring: Gateway to Modernism" from Stravinsky’s Ballets by Charles M. Joseph, reposted here through the kind permission of the author and Yale University Press (the full publication credits are listed at the conclusion of this post):

Even before the curtain went up on Roerich’s barren, “prehistoric” scenery only a few minutes into the score, the fidgeting began with Stravinsky’s craggy, layered introductory music. … “I wanted to express … nature’s terrible fear for the beauty which is rising, a scared terror in the noonday sun, a sort of cry of Pan,” Stravinsky is said to have commented in an article published the day of the premiere. “The musical material itself inflates, grows, spreads. Each instrument is like a shoot which grows on the trunk of an ancient tree; it is part of a formidable whole.”

Let’s listen to the opening segment described above, entitled “Adoration of the Earth,” a passage that features that most famous of bassoon solos, in this performance with the Berlin Philharmonic conducted by Sir Simon Rattle:

Dancers in the original production of Igor Stravinsky’s ballet The Rite of Spring; costumes and backdrop by Nicholas Roerich. Image courtesy udiscovermusic.com

Before returning to the text by Charles Joseph, we want to introduce a couple of the players who provide testimony in the passages that follow. Marie Rambert was a Polish-born dancer and instructor recruited by Ballet Russes impresario Diaghilev to assist Nijinsky in preparing the choreography for The Rite of Spring premiere and, as such, provided a first-hand account of the events of that night. Another witness quoted below is Russian-born dance journalist André Levinson:

The audience’s agitation quickly escalated as the curtain rose, revealing Roerich’s garishly costumed dancers. Such a sight could not have been anything close to what the audience might have anticipated. And to exacerbate the discomfort, the dancers began their relentless jumping to the brutally repetitive “The Augurs of Spring.” Each one of Stravinsky’s accented ostinato chords was driven downward into the stage, like so many implanted stakes, by feet-thumping peasants made to pass as ballet dancers. Rambert remembered that Nijinsky intended the thud of their stamping feet to give the sense of softening the earth so as to make it fertile; but the imagery was lost in the very un-balletic, earth impaling gesture. Both the music and the dance, working in a diabolical tandem, precipitated the audience’s mounting disgruntlement. And both music and dance, acting as coconspirators, unapologetically shoved the mockery of tradition into the faces of the unprepared audience. Choreographic gestures, if one could call them such, were intentionally distorted. …The dancers, hunched over, shuffling, turned inwardly, angularly posed, and static, were completely void of any poise or balletic propriety.

To lend a sense of the sheer complexity of Stravinsky’s score with its multiple changing meters and offer perspective on the unprecedented challenges faced by both dancers and musicians in preparing The Rite of Spring for premiere, here is a view of the reduced score for the ballet’s climactic “Sacrificial Dance”:

Sketches of dancer Marie Piltz in the "Sacrificial Dance" by Valentine Gross-Hugo. Click to enlarge

By the conclusion of the ballet the “Sacrificial Dance” served as a dénouement to the evening. As André Levinson recalled, Marie Piltz, trembling throughout, just as the composer and choreographer planned, faced “a hooting audience whose violence completely drowned out the orchestra.” She stared trance-like, in a stupor, with convulsive-like spasms obliterating the very tenets of classical dance. Her “primitive hysteria, terribly burlesque as it was, completely caught and overwhelmed the spectator,” Levinson observed. The entire ballet was indeed “a crime against grace,” and not only for the dancers but the musicians as well. Instruments screeched in extreme ranges with special effects, leaving the audience hissing. Everything seemed upside down. Fifty years after the scandal caused by the premiere, Stravinsky contended it was not the music that provoked the outburst so much as what the audience witnessed on stage: “They came for Schéhérezade, they came to see beautiful girls, [but] they saw Le Sacre du printemps, and they were shocked. They were very naïve and very stupid people.”

In fact, later in this post we’ll be showing that very interview, from documentary footage of Stravinsky revisiting the places associated with The Rite of Spring premiere. In the meantime, here are some additional names to introduce, individuals who will be referred to in the next segment of text: Serge Grigoriev was the régisseur for the Ballet Russes (essentially, the stage manager.) Mikhail Fokine had served as chief choreographer with the Ballet Russes but left the company after a rift with Diaghilev. Pierre Monteux was the conductor for the Ballet Russes.

Back now to the account by Charles Joseph:

Choreographer Vaclav Nijinsky had portrayed the title role in the "sexually salacious" Afternoon of a Faun during the previous Ballet Russes season.

The reviews immediately following the premiere provided assorted truths, exaggerations, unsubstantiated claims, conflicting memories, and speculation. Some felt the riot was better orchestrated than the music itself, given that several protestors arrived at the hall with an agenda in hand. Diaghilev had perhaps worn out his stay, given his recent, indelicate perpetrations, as evident in the sexually salacious insinuations of Faune and Jeux. Other adversaries harbored resentment regarding Diaghilev’s forced resignation of Fokine. Vocal demonstrations broke out during the performance, balanced quickly by counterdemonstrations. Aesthetes voiced their disgust, while advocates in attendance shouted charges of philistinism. Stravinsky left the auditorium to stand next to Nijinsky, who according to the composer, barked out the counts for the dancers from backstage, although Grigoriev recalled that “Nijinsky stood silent in the wings.” Diaghilev ordered the lights turned on and off in a futile attempt for the police to disperse the warring factions; but there is nothing to substantiate the involvement of the local gendarmes. Monteux persevered, as did the dancers, bulldozing ahead against the tide of catcalls hurled against them. Nijinsky claimed it was Stravinsky’s cacophonous score that incited the uprising, while Grigoriev, Rambert and others maintained the music was barely audible given the chaos. Stravinsky argued that Nijinsky’s choreography triggered the entire disruption. Whatever the case, when all was played and danced, Diaghilev achieved precisely the splash he desired. More objective accounts were authored by composers such as Debussy and Ravel, dancers including Nijinska and Rambert, and other artists such as Valentine Gross-Hugo, whose sketches of the performance superimposing poses of the dancers upon Stravinsky’s score (see the image above) are often reproduced and Cocteau, whose famous drawing of Stravinsky at the piano (below) captures the spirit of the work’s modernism.

Indeed, years after the fervor subsided, Cocteau provided a more dispassionate commentary upon the scandal.

Stravinsky at the piano by Jean Cocteau. Click to enlarge

“Le Sacre du printemps was performed in May 1913, in a new hall, without patina, too comfortable and too cold for an audience used to elbow-to-elbow emotions, in a mistake of pitting a work of youth and force against a decadent audience…. To an audience, low-cut dresses, tricked out in pearls, egret and ostrich feathers; and who acclaim, right or wrong, anything that is new because of their hatred of the former. And in addition to fevered musicians, a few sheep of Panurge caught between fashionable opinion and the credit owed to the Russian Ballet. And if I don’t go into detail, it is only that I would have to point out a thousand details of snobbism, super snobbism, anti-snobbism, that would need a chapter to themselves.”

Cocteau goes on to describe Stravinsky’s fauve work, “a symphony impregnated with savage pathos” that produced a masterpiece caught in the “petty schisms and narrow formulas” then resisting the dawn of modernism; and Nijinsky an artist willing to “reject grace, having known too well its triumph.”

Sergei Diaghilev: "The more outlandishly controversial the upshot, the better his cause was served." Click to enlarge

In the end, history has accorded far too much weight bruiting about the premiere’s infamy. Diaghilev was in the business of crossing thresholds and evoking reactions. The more outlandishly controversial the upshot, the better his cause was served. What may have been lost amidst the hullabaloo was an uncompromising, ritualistically primal, choreographic/musical assault upon the encrusted traditions of both arts. Le Sacre sounded a cry of emancipation intent on establishing new territory for those willing to accept the audacity of a genuine cultural sea change. The bedecked Parisian upper crust in attendance that opening night got what they bargained for: an inflammatory, sublimely unintelligible desecration to fuss over and bandy about in casually chic conversation. Many walked away dazed by the incursion of sounds and sights upon their senses. They were offended, just as they should have been. But for those who could see and hear the implications of what they witnessed, there was a piercing awareness that the Rubicon had been crossed. Nothing would ever be quite the same.

Sketch of Stravinsky by Picasso, 1920. Click to enlarge

Only a few more performances were given after the premiere, and without incident. Le Sacre then exited Paris en route to London where the ballet was staged three more times in July as part of the Ballets Russes season. The ballet was performed as Stravinsky and Nijinsky had composed and choreographed it, although Diaghilev had briefly considered making cuts, perhaps to stave off another public skirmish. Not only was the complete ballet performed without the outbursts that greeted it in Paris, but it garnered a modicum of understanding. Soon thereafter Diaghilev dismissed Nijinsky from the company. With his departure the original choreography would become lost; but the ballet’s impact remained undiminished. …

At this juncture, we return with Stravinsky to revisit the apartment where he began the composition of The Rite of Spring in the autumn of 1911…and we hear from Marie Rambert as well, recounting details of the ballet’s premiere some fifty years after the fact:

World War I: British troops go over the top in the trenches during the battle of the Somme. Photograph: Paul Popper/Popperfoto/Getty Images. Click to enlarge

And now, the final passages of “The Rite of Spring: Gateway to Modernism” by Charles M. Joseph:

By August 1914, the world was plunged into an all-consuming war of apocalyptic proportions, both physically and psychically. Diaghilev scrambled to keep the Ballets Russes afloat, touring constantly throughout Europe and America. Nijinsky would work for the impresario a few more years, although their relationship would never be the same.

From 1919 on, a deepening schizophrenia would force Nijinsky to spend his life in and out of various psychiatric asylums. Roerich came to America in 1920, increasingly absorbed by his interests in theosophy and peace studies. He too would never again work with Stravinsky. The composer returned to Ustilug for a brief summer residence, but by winter retreated again to Switzerland where he would live in self-imposed exile for the duration of the war. From a distance he watched his homeland burst apart: the outbreak of World War I, the murder of Rasputin, the revolution in Petrograd, the abdication of Nicholas II, and the establishment of the Soviet government. The orchestral score of Le Sacre would not be published until 1921, and those who came to know it did so largely through the release of the four-hand arrangement of 1913. The ballet itself went unperformed during the interim.

Igor Stravinsky had an estate in Ustilug, situated on the east side of the Ukrainian-Polish border, and visited it frequently between 1890 and 1914. His mansion is now open to the public as a museum.

Nicholas II and the Russian royal family: From a distance, Stravinsky "watched his homeland burst apart.” Click to enlarge

Joffrey Ballet’s reconstructed The Rite of Spring from 2013, the centennial of the work’s premiere

Original watercolor by Jasia Julia Nielsen. Used with permission. Click to enlarge

A century after its birth, Le Sacre du printemps has lost neither its artistic impact nor its broad historical reach, for its imprint long ago transcended the worlds of music and dance in securing the status of a cultural hallmark. More than any other work Stravinsky would create, Sacre immediately became a behemoth indissolubly synonymous with his name, to the point of becoming burdensome. The composer’s identity with the work immediately congealed, producing an inescapable aura. Having conjured up such a cataclysm, what else could the thirty-one year old composer possibly write? By the time his 1928 ballet Apollon Musagètes premiered in Washington, D.C., the audience fully expected to witness a wanton, barbarically “Russian,” Sacre-like experience. As dance critic John Martin wrote wryly in his review, the American public arrived hoping to see a virgin sacrificed. Anything else would be a letdown. …

In a 1913 review, a critic remarked, “Le Sacre du printemps baffles verbal description. To say that much of it is hideous as sound is a mild description…. Practically, it has no relation to music at all as most of us understand the word.” Indeed, reconsidering what we understood by the word “music,” perhaps best captures the work’s essence. Stravinsky’s ballet obligated its listeners to reexamine their fundamental thinking about musical meaning, just as Nijinsky’s choreography forced us to reconceive the compass of dance. More than anything, the ballet presented a gauntlet. Its demand for a sweeping reassessment of our perceptual limits ran penetratingly to the work’s boldly momentous achievement in launching a new artistic order. In that sense alone, Le Sacre’s presence seems as compelling now as it did then.

Charles M. Joseph is Professor Emeritus of Music and the former Dean and Vice President of Academic Affairs, Skidmore College. He is the author of two previous books published by Yale University Press, Stravinsky and Balanchine, the winner of an ASCAP Award in Biography, and Stravinsky Inside Out. He lives in Saratoga Springs, NY.

Claudie Ossard, French film producer, has guided the creation of the films Amélie (2001), Delicatessen (1991), Arizona Dream (1993) and the cult favorite of many opera-lovers, Diva (1981), among many other titles.

On behalf of The Sembrich Board of Directors and staff, we’re pleased to acknowledge the generous sponsorship of this special four-part Alfred Z. Solomon Innovator Series by the Alfred Z. Solomon Charitable Trust. In closing, we want to relay our sincere thanks to Charles M. Joseph and Yale University Press for generously allowing us to illuminate the events of May 29, 1913 with selections from Mr. Joseph’s meticulously researched volume, Stravinsky’s Ballets.

Stravinsky’s Ballets by Charles M. Joseph

Copyright @2011 Yale University

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Section 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without permission from the publishers:

https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300118728/stravinskys-ballets/

We had the pleasure of meeting Charles Joseph when he joined us for a reading at The Sembrich following the publication of his book Stravinsky and Balanchine in 2002. We truly appreciate his participation in this, our first virtual season.

We also want to express our enormous gratitude to film producer Claudie Ossard for graciously allowing us to share the stunning re-enactment of The Rite of Spring premiere from her film Coco Chanel and Igor Stravinsky, a film sequence that affords us the opportunity vicariously to experience that historic event!

Finally, tremendous thanks to artist and mezzo-soprano Jasia Julia Nielsen for granting us permission to include her striking watercolor of Stravinsky in today’s post.

Until next time,

Richard Wargo

Artistic Director